When telling others about my time at The Nature Institute in Upstate New York I usually say something like, “it’s the real deal.” I signed up for their year-long Foundation in Goethean Science course desiring to learn from practitioners of a living tradition. To my pleasure, this is what I found.

One can voraciously read Goethe’s writings and those who have taken up his method after him; one can let these thoughts and images expand one’s perception while engaging in contemplative observation of natural phenomena; one can even conduct the series of experiments Goethe laid out in the Farbenlehre (or, as Craig Holdrege has alternatively translated the title, Discourse on Color); and yet all of this admirable striving may not be enough to genuinely understand how the method ought actually to be practiced. Some things, it seems, can only be transmitted through apprenticing with actual practitioners, for as Craig often emphasizes, one learns Goethean science by doing it.

The year-long course is bookended with two two-week intensives that begin just after summer solstice. Between those intensives we had the opportunity to participate in monthly Zoom meetings facilitated by my friend John Gouldthorpe; during those meetings we read and discussed essays and excerpts from a number of writers including Goethe himself, Rudolf Steiner, Henri Bortoft, Owen Barfield, and Hans Jonas. I officially began the course in 2022 but came down with covid just before the first intensive and sadly had to miss it. Rather than wait two years later for the program to restart, I was permitted to participate in the intensive of 2023 and ended up experiencing the in-person curriculum in reverse order.

We began each day with 20 minutes of observation at a spot of our choosing on the grounds of the Institute. Not only were we tasked with observing the world about us and its transformations over the two weeks, but so also our growing together with it. On the first day Henrike Holdrege suggested we inwardly zoom out from our location to a view of the Earth and then back into the concrete environs we inhabited there in Ghent, New York. Afterward our morning observation we’d circle up in the main room and share notable features of our individual spots. In doing so, we learned from each other what there was to perceive beyond our spots, what we might’ve missed, and the various ways in which one give their attention to phenomena (focused gaze, peripheral vision, listening with eyes closed, registering degrees of warmth, etc.). We employed this collaborative method each time we regrouped to reflect on the many experiments we were led through, honoring Goethe’s admirable recognition that “it is true here [in science] as in other human endeavors that only the interest of many focused on a single point will generate something excellent.”1

By the end of the two weeks we had communally built up a dynamic picture of the place, mediated by each unique personality. On the last day we had the opportunity to express the latter more specifically by composing haikus based on our experiences of our chosen spots. Here’s mine from the end of the second intensive:

A riot of greens

in Light lived ever outward

Now darkened and damp

This daily exercise of observation and its culmination in the recitation of our haikus epitomizes two of The Nature Institute’s stated goals: to foster a shared perception of the natural world and, in doing so, facilitate human development. At the end of my first intensive I wrote in my notebook, quoting Craig or Henrike, “we’re concerned with becoming general human beings.” Genuine science, it turns out, is germane to this aspiration of becoming more fully human. As Goethe writes, “the more we expand our considerations and the more we relate phenomena to another, the more we exercise the gift of observation that lies within us. If we know how to relate this knowledge to ourselves in our actions, we earn the right to be called intelligent. For any well-constituted person, who is by nature moderate or has been made moderate by circumstances, achieving such intelligence is not difficult because life itself guides us in every step.”2 Whereas today’s commonsense view of science considers it a rarefied, impenetrable activity—remote from the everyday, Goethe’s science flows from the same kind of cognitive activity that fosters the growth of life wisdom.

There is thus more than just an etymological continuity between experience and experiment for, as Goethe writes, “We speak of an experiment when we take experiences of our own or of others, deliberately reproduce and present again the phenomena that arose, both those that came about fortuitously and those that appeared through the artifice of the experiment.”3 This close continuity is itself a larger outgrowth of the continuity between perception and thinking: as artificial arrangements—abstracted from the life of Nature—worthwhile experiments can only be contrived once one has thoughtfully reflected on perpetual experience. Though Goethe esteems the experimental process, his awareness of its abstract nature leads him to insist that “nothing is more dangerous than wanting to prove a thesis directly by means of an experiment.”4 The experimental production of facts is not really truthful for Goethe unless these facts combine to disclose something fundamental about living Nature in what he describes as a “higher order experience.” He cites his contribution to the field of optics as an example:

“In the first two of my contributions to optics I presented such a series of experiments that border on one another and that are directly connected with each other. When we attain an overview of all them we see that they constitute, as it were, one single experiment, one experience presented from manifold perspectives.”5

Goethe’s higher order experiment/experience aspires after a wholeness akin to that of living Nature’s prior to our intervention into its coherence with abstract thought and isolated experiments, only now it becomes luminous with archetypal ideas. This is what Rudolf Steiner means when in Die Philosophie der Freiheit he describes the pursuit of knowledge as the activity through which we fuse our alienated individuality back into a unity with the world.

One can’t completely communicate this kind of knowledge as if it were a mere article of information; we can receive it abstractly by reading or listening to lectures about it, but only by having the actual experience can we be said to genuinely know something. Goethe likens this to the proofs of mathematics that one must actually execute if one is to be said to know them. “It proofs are simply the expanded explication of connections that are already implicit in the basic parts,” says Goethe of the latter, “showing in the sequence that the whole is correct and unshakeable. Mathematical demonstrations are therefore more of the nature of expositions or recapitulations than they are arguments.”6 He contrasts this with the manner of proving in experimental science that we are more familiar with today wherein a “clever speaker devises… arguments… [that] contain only isolated facts and… through cleverness and imagination, make a point and create the surprising semblance of right or wrong.”7 The tendency to produce facts for the reinforcement of models that have become entrenched in the field of science (e.g., the Big Bang theory of cosmic evolution) despite observations that contradict them is just one of countless examples of the motivations behind this aspiration to prove rather than produce noetic experiences.

One of the primary elements of Goethe’s method is thus a chastity of the theorizing imagination and a bracketing of what we believe we know about the world. For this reason, participants in The Nature Institute’s intensive may (indeed, ought to) experience as much unlearning as they do learning. What is my motivation for venturing an explanation of a given phenomenon? Did the description I offered the group exclusively issue from what I’ve observed or have I interpolated some functionalist interpretation into it (e.g., the flower is such and such color because it is attractive to pollinators)? Craig, Henrike, and John McAlice—our third instructor—demonstrated this chastity in their pedagogical method. Not only did they refrain from offering us theory prior to the many experiments (experiences!) we were led through, they also refrained from explanatory language when the time did come for reflection. “Did anyone notice there was a word I never used when talking about phenomena?” asked Craig during one of the last days of the intensive. That word was because. Rather than say “the sky is blue because light fills the atmosphere against the darkness of space,” Henrike would instead say something like, “when conditions are such that light fills some kind of medium in front of darkness, blue appears.” As Goethe suggested, such descriptions have a mathematical, equation-like character to them; rather than leading us away from the world and into a virtuality of abstraction, they can guide the uninitiated into an experience of the archetypal (the spirit) as it reveals itself through this world of appearances.

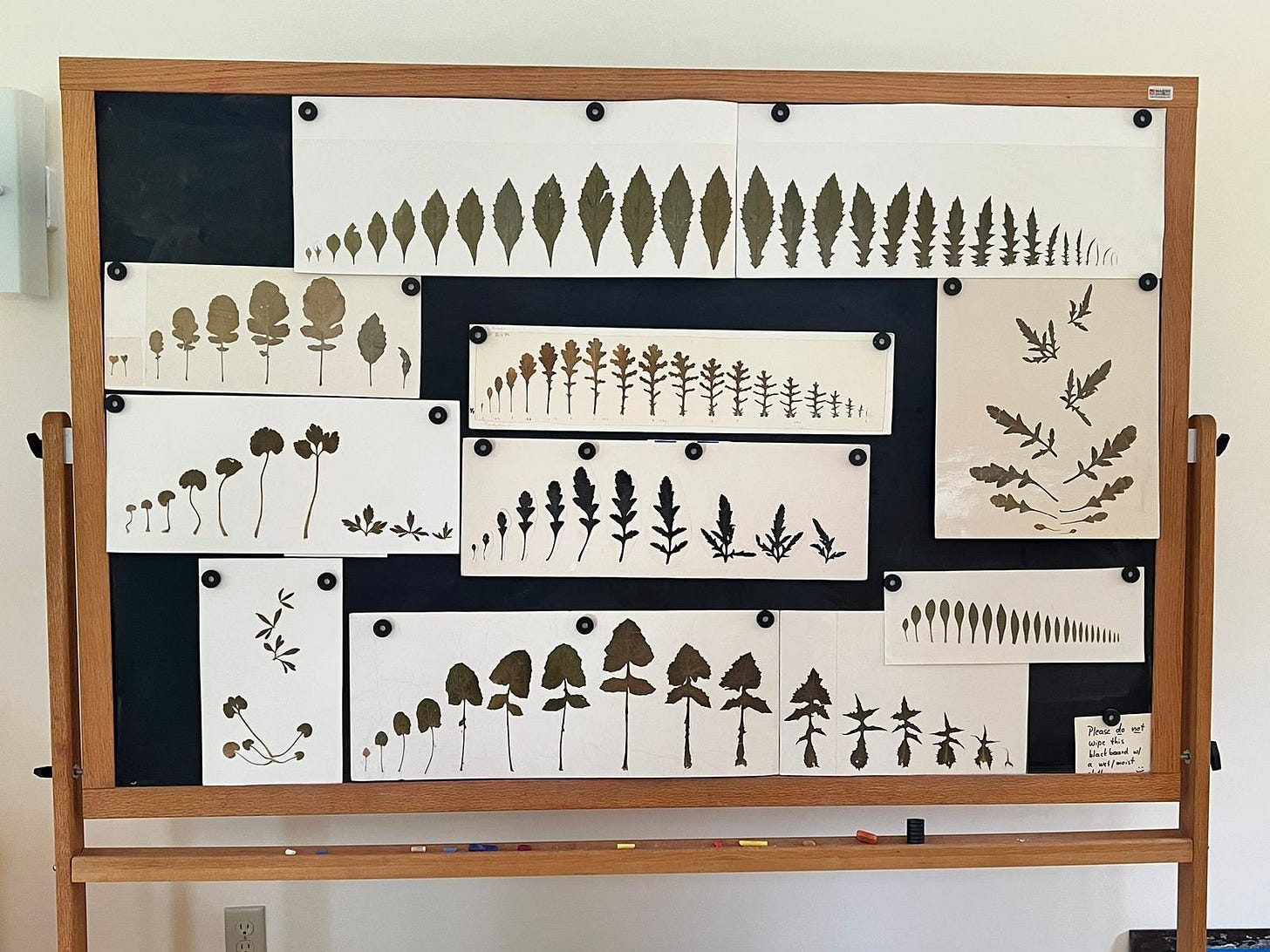

These revelations are not unlike the phenomena we encounter in the field of artistic expression; their forms speak of some kind of intention and intelligence. In addition to exercises in observation, experimentation, and intellectual reflection, time was also allotted most days for artistic practices. I could recognize a rationale for such practices when exploring light, darkness, and color: working with value (shading) and creating secondary colors through primary pigments was an extension of our optical observations. The rationale wasn’t so clear to me when we were drawing plants; not until encountering something Goethe wrote in his essay On Morphology did the purpose of such exercises dawn on me more clearly. “It is no doubt unnecessary,” says Goethe in reference to the intuitive perception (Anschauung) that his method seeks after, “to describe in detail the close relationship between this scientific desire and our need for art and imitation.”8 Perhaps unnecessary for Goethe and his contemporaries, but not for me! McAlice guided our drawing and painting sessions with a balance of patience and rigor, insisting that we put forth an effort to be exact; my frustration in grade school with such instruction rushed up, inciting all manner of rebellion. What’s the point of drawing this plant precisely if I can just come to know it through intuition? But upon reading Goethe’s comment in On Morphology I realized that such practices actually deepen our inward participation (imitation) of a given phenomenon. My impatience now seemed to me like a little devil, one kindred with the demon who rushes to answer questions with clever explanations; in both instances knowledge is implicitly conceived as something that my subject possesses rather than something that arises through a relationship with living Nature.

To behold grandeur, artistry, and intelligence at work in the world of living Nature, whether it be a sparkling grain of sand or a torrential waterfall, is to experience wonder, and, as Steiner once said, “all knowledge must have wonder as its seed.” The instructors at The Nature Institute imbued their course with this mood and, because they are seasoned practitioners, they also embodied another mood—one that we participants departed with more of a share in than we had prior to arriving. That mood is reverence, for in addition to marveling at the beauty and mysterious power of the world, Goethe’s method provides us a way to grow in our knowledge of it; the feeling of reverence is the proper response to that growth, for one begins to perceive the depths of wisdom at work in it. Rather than attempt to communicate the rudiments of knowledge I acquired through the experiences curated by our instructors, I invite you to sign yourself up for their next course and make those discoveries yourself as Craig recommends—by actually doing Goethean science.

I will, however, share some modest insights in my next post—insights that flowed from the project I undertook (observing the apparent movement of the sun) between the two intensives. Until then I wish you all well and invite any reflections/comments you might have about what I’ve written here.

Adieu!

—𝓐.𝓚.𝓐.

From Goethe’s “The Experiment as Mediator of Object and Subject.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“On Morphology,” by Goethe.

This is a great reflection on your studies, Ashton!

In one sense we could say that the "Goethean Method" consists of education. In the place of scientific experiments that test an intellectual hypothesis, the Goethean Scientist creates the conditions under which he or she can *experience* an aspect of nature that was previously hidden from him or her. In place of the scientific report, the Goethean Scientist then has the task of creating the condition under which others can come to the same experiences as he has created for himself. This, to me, is the essence of Goethean Science. Since there is more than one way to create an transmit these experiences, I sometimes like to say that there is no Goethean Method. This is why I put these words in quotes above.

You exposition is a great expression of your experiences on this path.

Thanks for sharing your experience at The Nature Institute. I can relate to much of what you describe going back to my own studies in Goetheanism at Emerson College in the UK some years ago. Apart from the content itself, i.e nature studies, what strikes me most, both now and then, is the process towards the conscious experience of the act of knowing which you describe so well.

I have recently reflected back to my early years of graduate school when that same consciousness was sometimes present, albeit in a dim way. I particularly remember studying integrals in a maths course which at first felt as a highly abstract form of mathematics. It was only when I could begin to ’imagine’ (visualize) the surfaces and volumes that the integral equations stood for that the whole subject became graspable. Otherwise, knowledge can only be, as you point out, a theorising upon the world. Having a space and community that fosters an awakened sense of cognition as for example Goetheanism is therefore a real blessing.

What stands out in your post for me is Craig’s and Henrike’s insistence in not using the word ’because’ and ’refraining from explanatory language’. In my own studies and sharings with others in similar contexts this seems to be one fundamental threshold that is difficult to surpass for everyone, including myself. To learn to allow the appearance to speak for itself has been the greatest gift the goethean method has given me. Glad to hear it lives in others as well.