Reverent Impiety: Reading Rudolf Steiner's Christian Cosmology Against his Racialism

Recording link, edited transcript, and slides from my talk for Harvard's 100 Years Rudolf Steiner conference

Eventually I’ll have the essay version up to share, but for now here is the link to the recording of my talk (starts at 44:26), edited transcript, and slides. As you’ll see below, there are slides that I did not have time to include in my 20 minute allotment. One is an expanded genealogy of ‘ethnos’ and ‘race,’ another addresses Steiner’s (inconsistent) teachings regarding ‘race spirits’ and ‘folk souls,’ and the other three are from the single slide of racist quotes I shared, but expanded and with full references

I invite your critical feedback as this is an ongoing research project.

This talk, “Reverent Impiety,” may seem somewhat provocative, but I intend this critique as a kind of intellectual service to Steiner’s legacy and to the anthroposophical movement. I hope my sincere intentions come through, and I look forward to engaging with your thoughts.

A bit about my background: I recently completed my dissertation in May on the work of Owen Barfield and his theory of the evolution of consciousness. Barfield was an English philosopher and anthroposophist. Before discovering Barfield, I was introduced to Steiner by Robert McDermott when I began my studies in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness program. I was initially very excited by Steiner as an esotericist and continuer of the German idealist tradition, especially Goethe’s method. However, I was put off by the allegations of racism, so I kept Steiner at a distance until I realized that to understand Barfield, I really needed to understand Steiner.

In 2020, during the pandemic, I dove in and started participating in many anthroposophical initiatives, like Applied Anthroposophy, which started that year online. Since then, I’ve listened to many of Dale Brunswald’s lecture recordings, read numerous books, engaged in many spiritual exercises that Steiner has given, worked with the Youth Section, and am now at the Goetheanum, where I’ve been for the last five months doing a postdoc project with Nathaniel Williams. So I am something of an insider—I’m approaching this as an internal critique from someone sympathetic to Steiner and his work, though I wouldn’t go so far as to call myself an anthroposophist.

This is also an analytical critique in that I won’t be speaking out of any kind of clairvoyant research, but just using what I consider to be my healthy human reason—unprejudiced reason, but importantly, 21st century American reason. This is something Steiner asked his readers to do: if you can’t clairvoyantly confirm my research, just use your healthy, unprejudiced judgment.

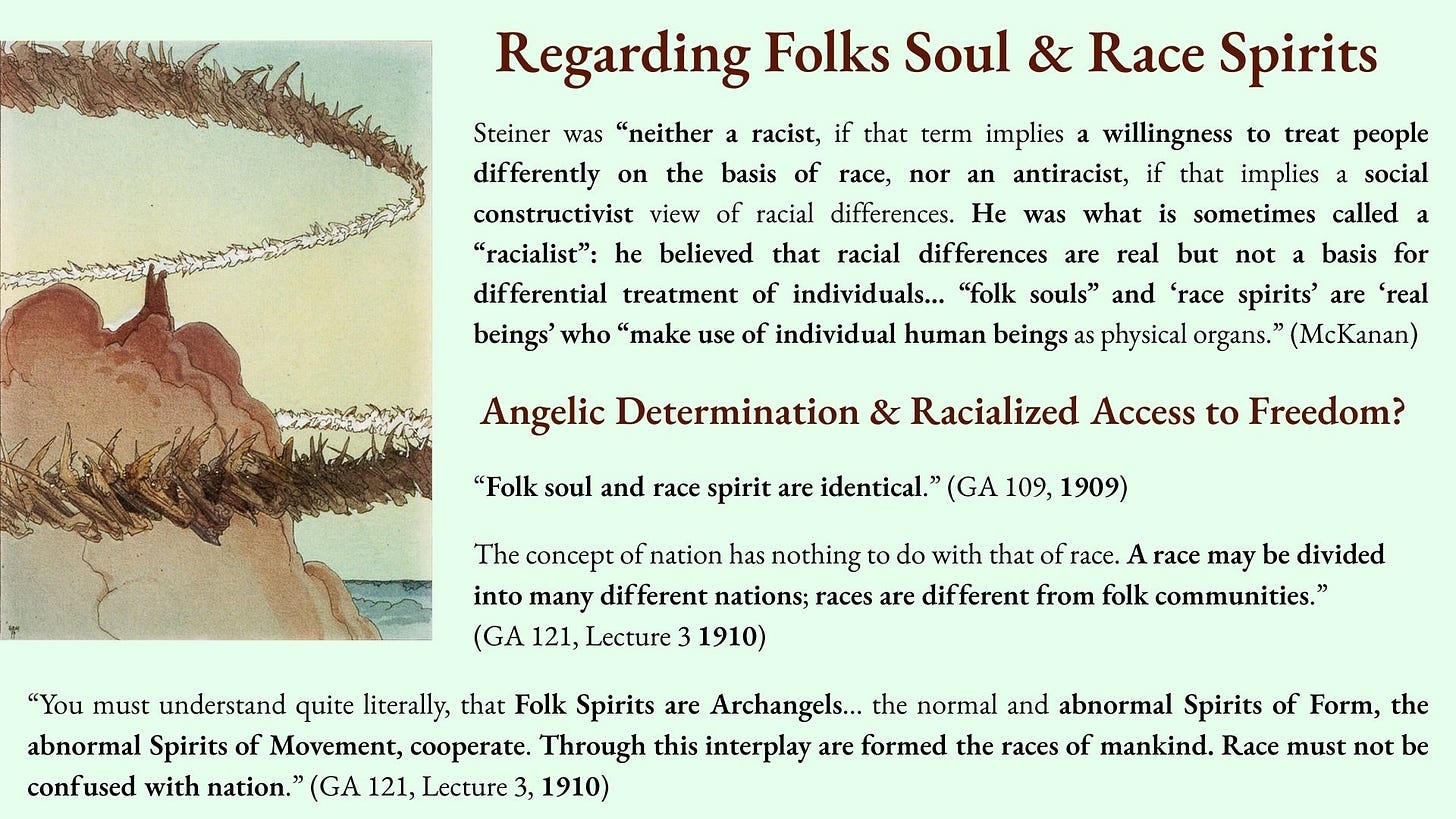

I’ve found this issue of racism a vexing one from the beginning, and I put “inconsistent” in the title because, as my attempt at reconstruction should make clear, Steiner wasn’t just a racist. You could also say he had his anti-racist moments as well. For me, it’s more about disavowing the racist elements and bringing forward what is true and good.

In the course of this talk, I’ll delineate what I consider to be the ethical and epistemological implications of the critique. What does it mean that what I would say is a large error—a racial doctrine which in some sense is quite central to Steiner’s understanding of evolution—what does it mean for our confidence in Steiner’s methodology and cosmology? And I’ll enlist the universalist dimension of anthroposophy, specifically the Christianity at the heart of it, for reconstruction, paving a way forward after disavowal.

Scholarly Context: Reverence or Disavowal

This talk is emerging out of an already ongoing scholarly conversation about Steiner’s work. Two scholars have already been referenced: Dan McKanan, who is graciously hosting us, and Peter Staudenmaier. In his book Between Occultism and Nazism, Staudenmaier insists that it’s important that we make these critiques and even disavow the racist elements because such occult doctrines were articulated as if they were just facts, and because they didn’t heed their own political ramifications, they lent themselves to being appropriated by aggressive ideologies like the Nazis.

As we know, Marie Steiner and others of the Goetheanum leadership—though it’s complicated, of course—cooperated with, and some even collaborated with Nazis and shared their racial theories. So we have historical precedent. Having been at the Goetheanum for the last five months, I can say I have met some younger men who are persuaded by the resurgence in racial theorizing and think that Steiner was right about these things. So there’s contemporary precedent for this concern as well.

It was from Staudenmaier that I got this idea—partially, along with one of my former professors (Jacob Sherman) who pointed out the unchristian character of Steiner’s racist theorizing—to enlist the universalist aspects of anthroposophy toward an internal critique. I would claim that Christianity is anti-racist.

Dan McKanan, in his book EcoAlchemy, points out what he aptly refers to as Steiner’s “hermeneutic of reverence,” which Steiner recommended to his students as a kind of epistemological orientation that makes one more receptive to receiving higher knowledge. It’s a humble mood, recognizing that we do not yet know what we seek to know, and that there’s something almost higher about the source from which we might learn it—a kind of pious orientation toward a spiritual teacher and spiritual teachings.

McKanan mentions that this may be partially why many anthroposophists have been reluctant to disavow the racist passages—there’s this maybe understandable and even admirable orientation of “Well, I’m not clairvoyant like Steiner was, so how can I presume to make a judgment about this?” But McCannon raises the question: when it comes to the racial doctrines, maybe we can make an exception.

Steiner—even though reverence and wonder are a bit different—claimed to be in a lineage that leads back to Plato and others. This goes back to when Plato has Socrates say “philosophy begins in wonder,” in this kind of perplexity at the limits of knowledge and a kind of awe in consideration of the eternal gods who have perfect wisdom. As finite beings, we can become receptive to divine wisdom through this epistemological orientation.

Steiner is continuous with premodern thinkers in recognizing that knowledge is a self-implicating, self-transforming process that involves virtue and moods—cultivating moods like reverence and a capacity for wonder. Steiner himself says we should become capable of reverence because we are to learn things we do not yet know.

But when the hermeneutic of reverence inhibits us from questioning the human teacher, it could potentially block our pursuit of the true and the good, blocking the philosophical inquiry, the seeking after wisdom. Hence, a reverent impiety.

Defining Racism

First, let’s offer a definition. You don’t have to agree with this definition, but just so you understand what I mean and we can be on the same page. I’m drawing on this definition from Sindri Bangstad: Racism is premised on the idea that humanity could and should be divided into distinct biological groups or races—continuous with the spiritual, since Steiner taught that the biological-physical is a kind of reflection of spiritual processes. We would expect, if race is a reality, for it to be somehow reflected in the biological. For Steiner, the cause of race, or the reality of race, is reflected in the physical and biological, but it is spiritual in origin.

The definition continues: different races stand in a ranked and hierarchical relationship to one another, based on criteria that are fixed and relevant for their behavior. That last point refers to what is called essentialism—where, for instance, because I have white skin, I am determined to have a certain kind of soul and certain kinds of capacities available to me. My physiognomy gives me such and such nature.

Note that this definition of racism does not require hatefulness or the advocacy of violence.

Ethnos vs. Race

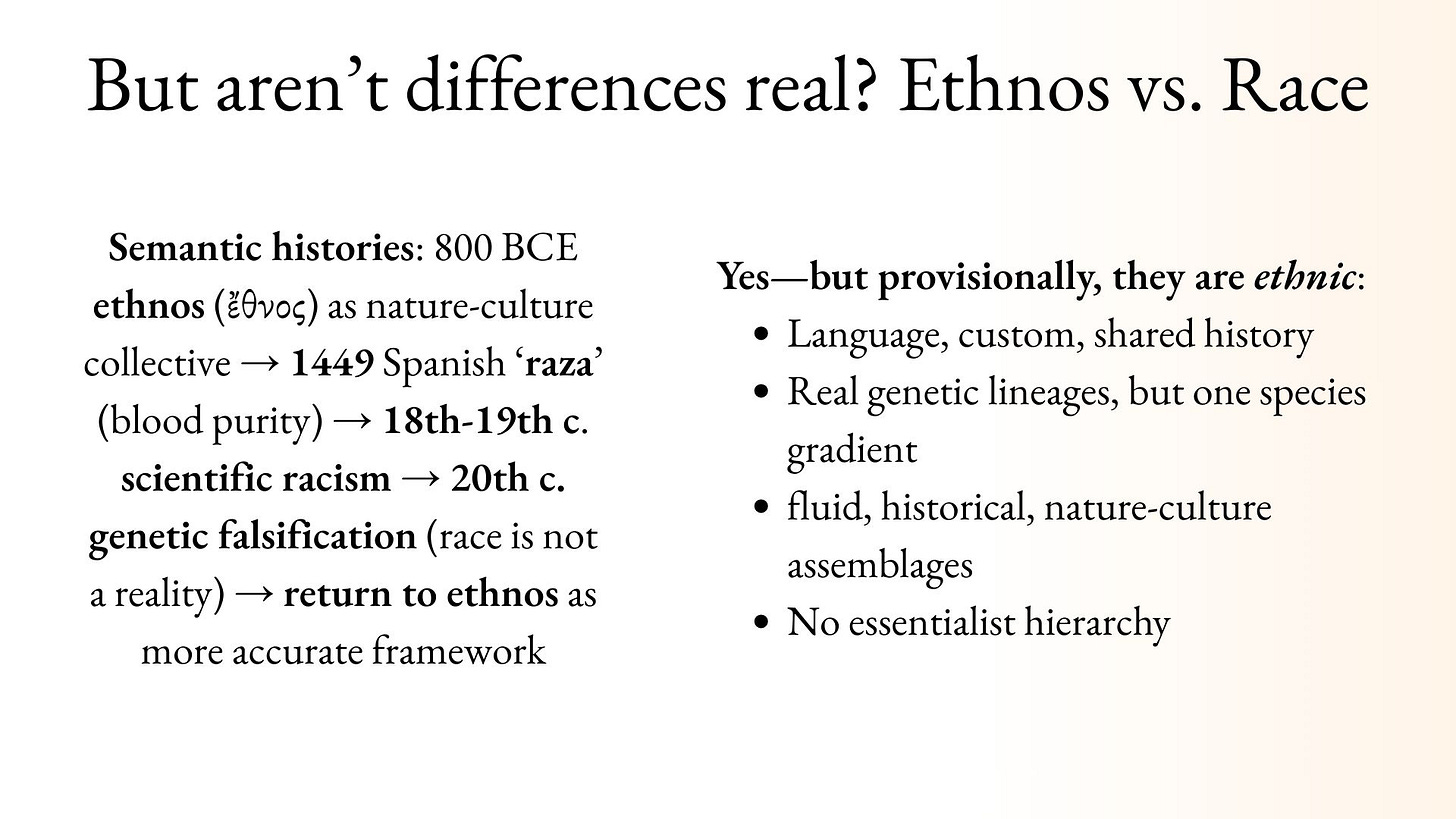

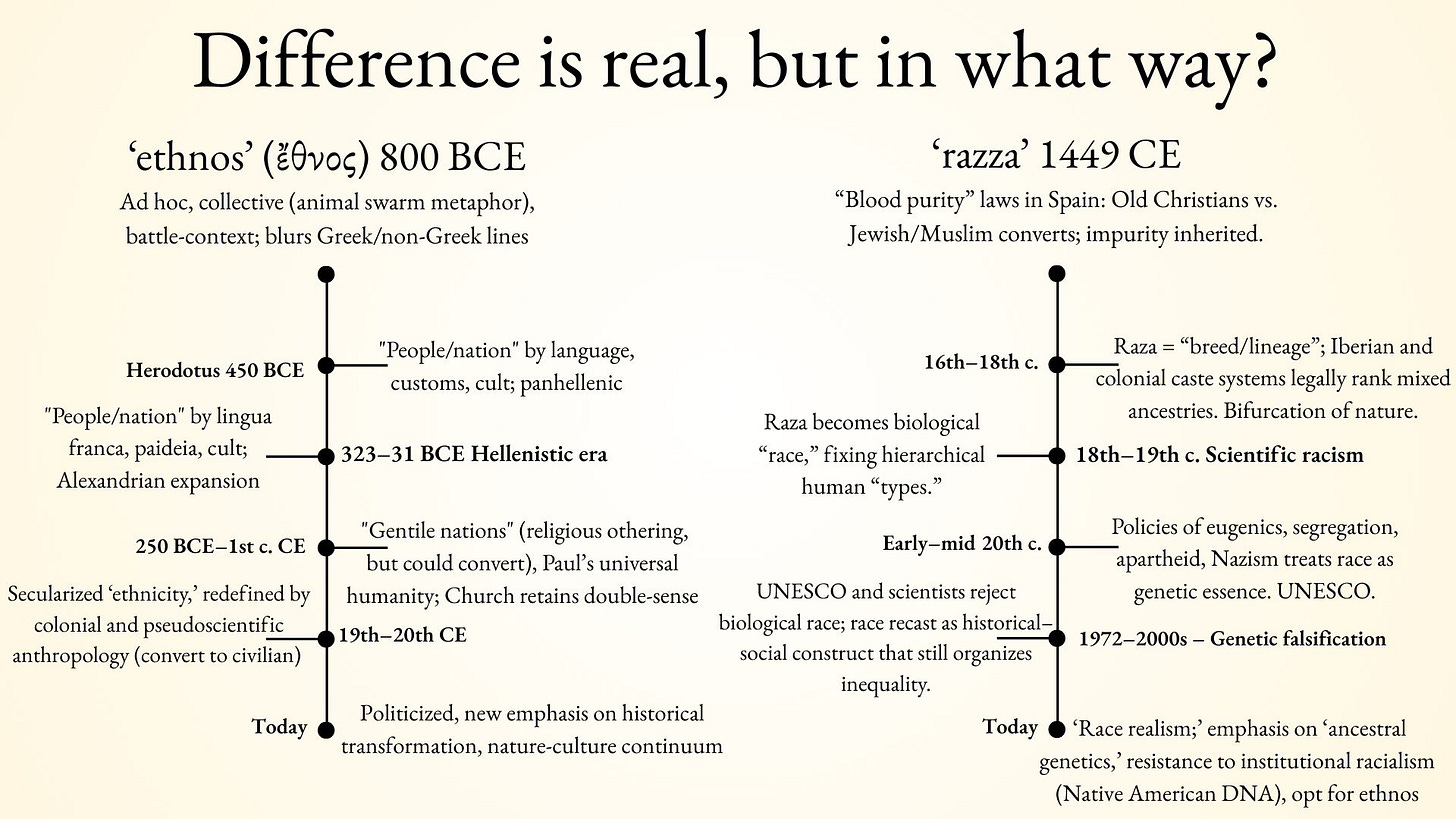

But aren’t differences real, you might ask? I would say yes, but I think a better term for us to use with respect to differences between human groups is ethnos rather than race. This has actually a longer history than the concept of race and predates the scientific bifurcation of nature.

If we look at the history of these concepts, we can go back to 800 BCE Homeric Greece and find ethnos being used to refer to human groups in general, both Greek and non-Greek, so it didn’t have an exclusionary connotation yet. Groups were bound not just by blood, but also by cult, language, customs, and shared history—a notion of belonging that is not just reducible to blood.

Race, by contrast, only starts to be used in Spain in the 15th century (around 1449 in the Spanish raza). It’s in the context of blood purity, but in a religious sense—those who had converted to Christianity from Islam or Judaism more recently were considered to have less pure blood than those who descended from more long-standing Christian lineages. This is before the scientific bifurcation of nature and culture, so blood is not yet just about the physical blood, but also involves cultural factors like language and cult—something like ethnos. Blood is not just a physical thing; it’s also bound up with religion, language, spirituality, and culture.

Into the 18th and 19th centuries, we get scientific racism when race is secularized and biologized—”it’s just the blood.” There’s this theory that there are subhuman variants, subspecies of human. Steiner’s thought is emerging out of this historical context, this intellectual history. These theories influenced his thinking.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-20th century, the 1950s and continuing to now, that the theory of race became falsified at the genetic level. It was discovered that there is actually more genetic variation within populations rather than between them. If there were actual races, you would expect there to be hard boundaries between populations, but what you actually find is more of a gradient—it seems that humanity is one species rather than differentiated into races. Sharp boundaries don’t exist.

This doesn’t mean differences aren’t real. We could say we return to ethnos as a more accurate category, because the groupings aren’t just about blood—they never were. Many Native American groups still recognize this in what counts as kinship for them: language, custom, shared history are really important factors of belonging, just as important, maybe even more important than blood.

Genetic lineages are important, especially when it comes to medicine and what treatments are proper for what genetic lineages. But they’re always changing as well, and not just through reproduction and food—also through cultural processes, like different languages and human experience. The body and the soul are not separate from each other. So I think of ethnos as a more explanatory term that unites the natural and cultural in this nature-culture feedback loop, and is more historical.

Examples of Racism in Steiner’s Work

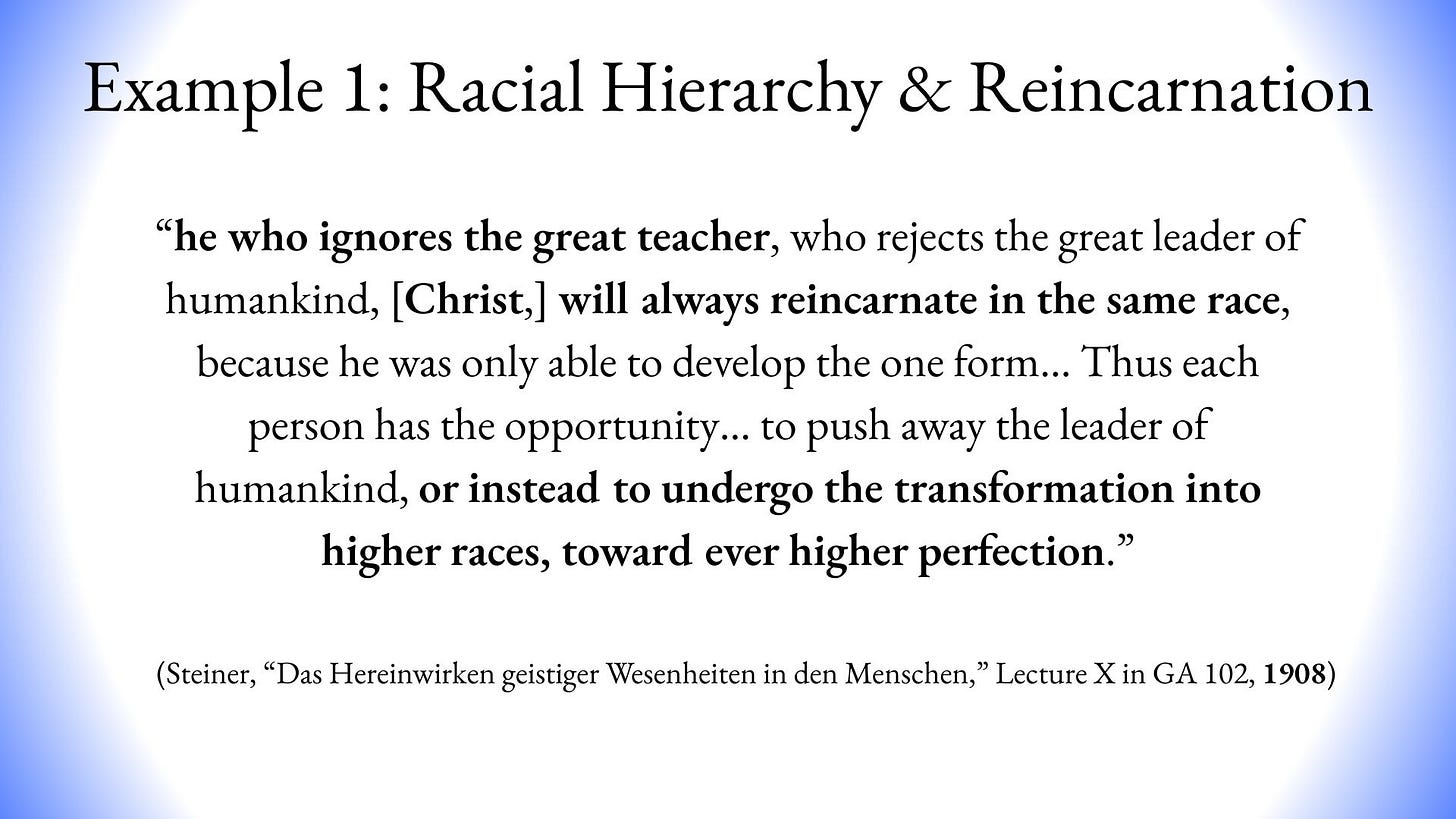

Karmic Racial Hierarchy

Here we have an explicit theorizing of racial hierarchy, and this time Steiner is tying it explicitly to the process of reincarnation. If you are heeding the Christ, he suggests that you will be advancing in further incarnations to more advanced races, to the extent that the individual can recognize Christ. I would say this is not a very Christian way of thinking about Christ.

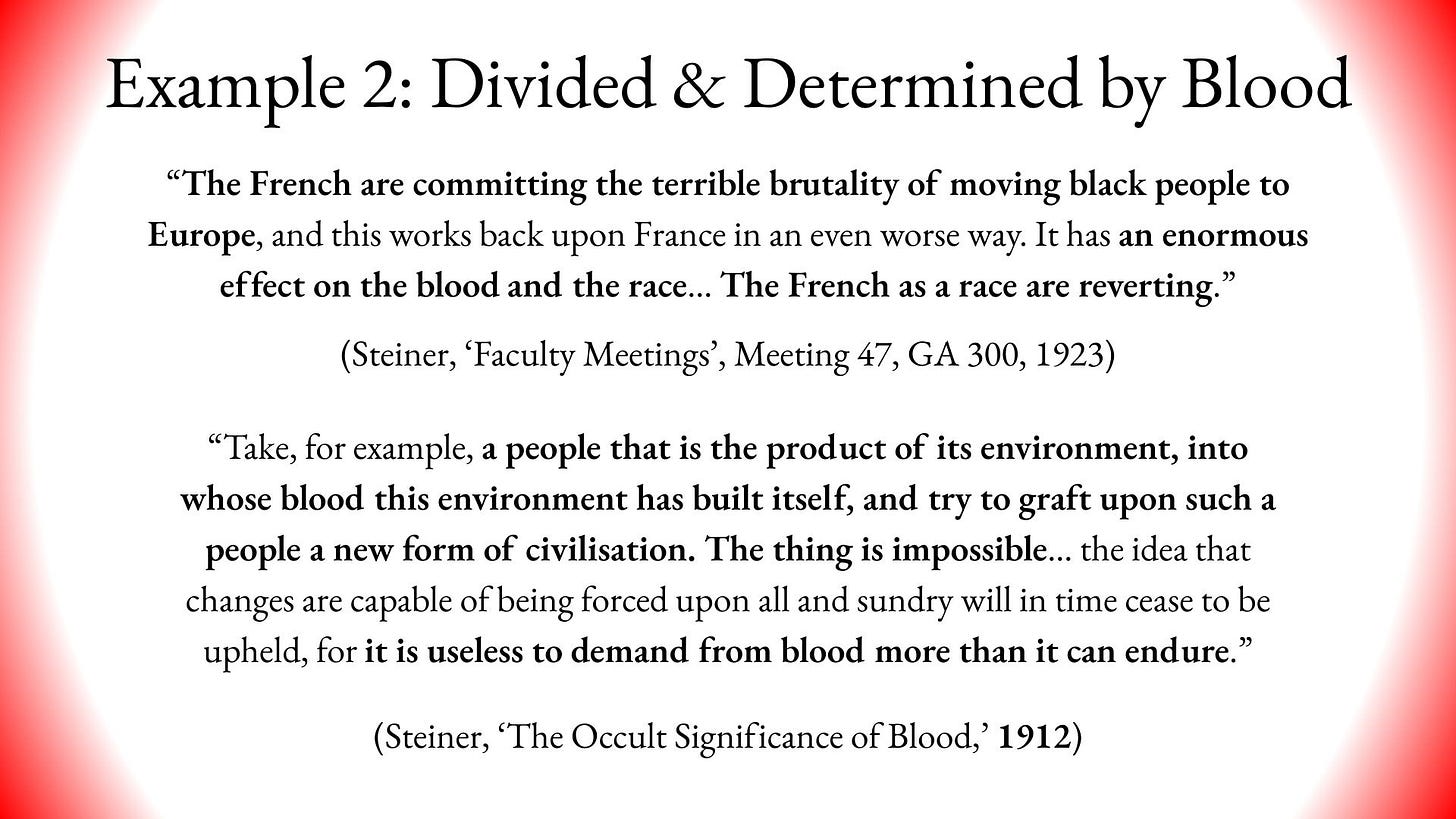

Divided and Determined by Blood

In 1912, Steiner says: “Take, for example, a people into whose blood this environment has built itself, and try to graft upon such a people a new form of civilization. The thing is impossible. It is useless to demand from blood more than it can endure.”

Here there’s explicit racist theorizing in that there’s a notion of a distinct people that are limited by the character of their blood—they cannot become civilized, and so they’re doomed to become extinct. There’s implicit notion of race, that there are these distinct categories, and that the racial type determines what an individual or a whole group is capable of.

Another example referencing blood: “The French are committing terrible brutality moving black people to Europe. It has an enormous effect on the blood and the race, and contributes considerably toward French decadence. The French, as a race, are reverting.”

Again, implicit reference to distinct races at the level of the blood, and also implicit hierarchy in the sense that there seems to be, for the French, a further state of evolution, more advanced, that is at risk of regression by association with Africans. There’s this notion that races should be kept separate because some are further along in their evolution than others, and mixing could cause regression.

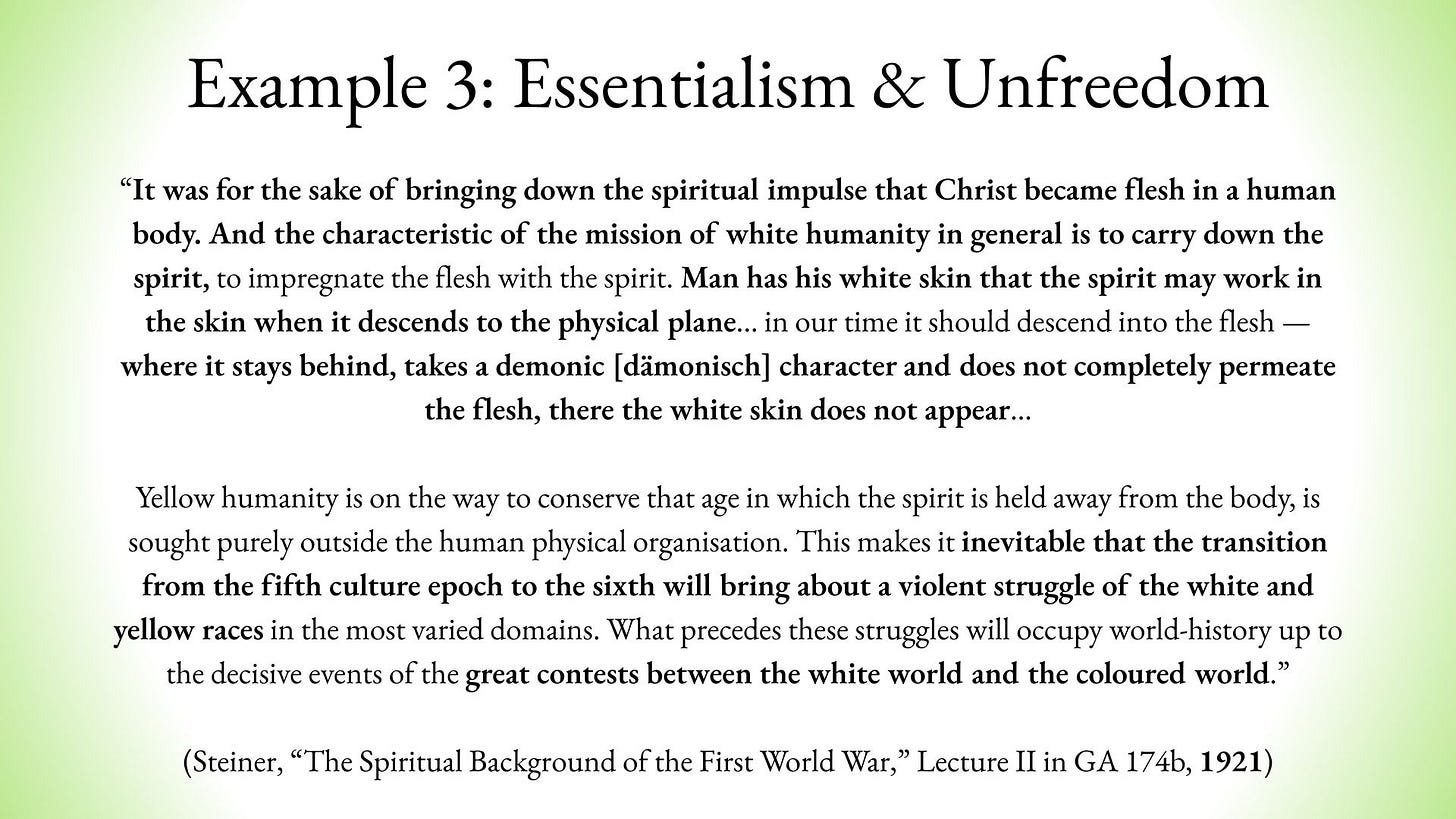

Skin Color Essentialism

Here is an example of skin color essentialism in the sense that white skin is being described as allowing for capacities connected with Christ. For Steiner such capacities revolve around the potential to act on behalf of love and freedom. If that is what Steiner means here, then he seems to be saying that white skin permits a more full actualization of action undertaken out of love and freedom, whereas darker-skinned people are not as able to achieve that. Maybe you have another interpretation, but this is how I understand Steiner here.

Grounds for Disavowing Steiner’s Racism

As has already been mentioned, because there’s been this falsification of the biological theory of race at the genetic level, I feel like we’re justified in reading this backwards into the spirit and saying: well, if there is a spiritual reality of race, wouldn’t it be reflected in the physical at the genetic level? If we can’t find the trace of race at the genetic level, can we really be confident in claims that we can’t verify for ourselves in this idea of race spirits determining individuals? So I think we have good reason to question the racial doctrine based on these new discoveries. There’s a reality to race in some sense—it has political consequences and is still within the cultural imagination—but not in a biological sense.

If it needs to be pointed out—it feels crude to do so—I think Steiner’s racial essentialisms just described are demonstrably false. Dark-skinned people are no less capable of being genuine Christians, acting on behalf of love and freedom, than light-skinned people. I have this example of the survivors of the Charleston Church Massacre, where a young white man killed many black people. Some of the survivors and those who lost loved ones made very moving public statements of forgiveness—a supreme act of love and freedom, one of the utmost acts of freedom.

Racial essentialism inhibits the perception of individuality and complex historical contingencies connected with race statistics. Even if you give lip service to honoring the individual—”I’m always going to meet an individual as an individual”—if you have a racial theory operating in the back of your mind, how able are you really going to honor that individual? I question that.

The same goes with historical contingencies. If you have an essentialist way of thinking about race, are you going to actually be receptive to the possibility that certain statistics around harm might also be connected with histories of enslavement and economic disadvantage when it comes to the spouting of race statistics as evidence given by race realists? I’m not so sure that one would be able to really be receptive to these historical contingencies in connection with such statistics.

Epistemological Implications

I think Robert McDermott puts it really well in his book Steiner and Kindred Spirits when he writes: “While these unenlightened statements are truly regrettable, they could have the positive effect of helping some of Steiner’s followers free themselves from the fundamentalist assumption that his words should be taken as unquestioned truths instead of progress reports to be continually checked and improved.”

So we’re thrown back on ourselves, you could say, if we want to practice Steiner’s method. And Steiner himself says spiritual perception is not infallible—the researcher can err. But importantly, Steiner wasn’t putting himself at the center of inquiry as a sort of key to knowing the world. He always put Christ as the logos incarnate, and he was in a long lineage of a kind of methodology based in the divine cosmic logos.

We have an intellectual ancestor, Maximus the Confessor, putting it in a way much the way Steiner does in the 7th century: “Imbued with his own qualities, so that, like the clearest of mirrors, we are now visible only as reflections of the undiminished form of God, the Word who gazes out from within.”

So “not I, but Christ in me” may allow us to become diaphanous to a revelation of truth in the world, making ourselves diaphanous so that it can reveal itself within our souls.

Ethical Reconstruction Through Christian Universalism

Finally, invoking the Christian universalism when it comes to the more ethical considerations. Matthew Rose, in his book A World After Liberalism, considers where we go from here when the secular continuation of universal justice and beneficence—which have a Christian genealogy, a metaphysics that made sense of them in the historical event of the Christ—is no longer believed in. How do we move forward? What’s the justification for continuing to honor those values? Maybe there’s some kind of necessity of retrieval, and I think Steiner and anthroposophy is one example of a contemporary retrieval of that.

Rose calls us to remember: “Early Christian thinkers promised believers an astonishing consolation. Conversion to Christianity brought about a transformation in ethnic identity, making believers members of a family that stretched back to the dawn of human history. It included the idea that Christians formed a new genos, or ethnos.”

Steiner continues this, and this is the part of Steiner that I think we should bring forward if we’re going to disavow the racist elements. I think it’s more at the heart of his vision and continuous with those who came before him than any of the racial theorizing.

As he says in Occult Science: “The Christ concept supplied an ideal that counteracts all separation. Alongside all of our earthly ancestors, the common father of all human beings appears. I and the Father are one.”

Well done. This part of the future of freeing Steiner from himself. I'm glad you don't shy away from using Staudenmeier. So many anthroposophists simply insult him and leave it at that, which I find completely inadequate. Steiner's racialism is incompatible with Christianity, esoteric or otherwise.

Much of what Steiner says on race is as unchristian as what Kant said, and Steiner was significantly influenced by Kant: https://blackcentraleurope.com/sources/1750-1850/kant-on-the-different-human-races-1777/

I'll be interested to see what you produce next

Thoughtful critique. The ethnos vs race distinction is crucial, and the genetic falsification angle provides empirical grounding for what Christianity already teaches about universal humanity. I've been wrestling with how to hold reverence for historical thinkers while acknowledging their embeddedness in harmful epistemologies, and the "reverent impiety" framing captures that tension well. The Charleston example drives home that skin-based essentialism collapses under real-world scrutiny.